When teaching grammar, I have often been guilty of teaching concepts in isolation and then drilling students with worksheets and the occasional game. Or I will have students do a quick warm up or exit ticket that requires editing inaccurate writing. Mentor sentences have been the most effective way that I have found to teach sophisti cated grammar structures, the intention and effect of those structures, and then encourage students to actually incorporate those structures into their own writing.

cated grammar structures, the intention and effect of those structures, and then encourage students to actually incorporate those structures into their own writing.

The methods of how to use mentor sentences translate across writing lessons, whether it’s writing for clarity, concision, cohesion, or creativity. This post is an introduction to mentor sentences, and specifically how to use them in the secondary ELA classroom.

![]()

![]()

What they are:

Mentor sentences are simple. They are excellent, effective examples of well-written sentences. They accomplish what the writer intends to communicate.

How they work in the classroom:

-

Choose a sentence.

- Choose a sentence that successfully models a grammatical concept that you are teaching that day or week.

OR

- Find an effective sentence that you want students to critically engage with. You can pull them from your class text, from a newspaper article or current events site you want to expose them to, or find a pithy quote from a historical figure. The sentences can come from anywhere.

- Choose a sentence that successfully models a grammatical concept that you are teaching that day or week.

-

Ask students what they notice about the sentence. This can be in think-pair-share format, Post-it note response, Popsicle stick cold-call, etc. Below is an example of the kinds of observations

students could make:

students could make:- Punctuation – There are a lot of commas. I see I semi-colon. There are parentheses.

- Vivid use of adjectives – The word putrid is unusual.

- Length of sentences – The sentence has a lot of clauses. The sentence is super long.

- Capitalization – Death has a capital letter. There are words I don’t know with capital letters.

- Similes – Lots of “like” or “as.” Lots of similes about the wind.

- Dialogue – The comma is in front of the quote. The speaker is angry.

-

Ask students to consider the effects of what they have already identified. This requires much more critical thinking and students benefit from small group discussion before sharing to the larger group. Your questioning their observations will help them consider the effects.

- Punctuation – Are we declaring, questioning, shouting? How will the punctuation help us read the sentence aloud?

- Vivid use of adjectives – What is being described? What images are conveyed to the reader? What connotations do those words evoke?

- Length of sentences – Is the writer setting a scene and using description or is she conveying an action sequence? Why are different sentence lengths appropriate? Who is the audience?

- Capitalization – What are the proper nouns? Who, what, where, when? Is something personified?

- Similes – What is being compared?

- Dialogue – Who is speaking? What do the words reveal about the speaker? Who is his or her audience?

-

Ask students, “How would the sentence change if…”

- Respond directly to their observations and use the questioning as a tool to push them to more deeply consider what they have already identified.

- As students become more comfortable with the concept of mentor sentences, encourage them to ask these questions to each other.

-

Students write their own sentences inspired by the mentor sentence!

![]()

![]()

Ways to use mentor sentences in your classroom:

Below are some ideas of how to incorporate mentor sentences into your own classroom and grammar lessons.

- Pre-teach a grammatical concept or structure, such as dependent clauses, FANBOYS commas, punctuating dialogue, passive voice, or participle phrases. Read ahead in your class text to pull out some effective mentor sentence for students to analyze and emulate.

- Have students keep a notebook (I prefer binders with sections) where they keep all their grammar lesson notes and all of their accompanying mentor sentence work.

- In groups or literature circles, have students identify a mentor sentence as they read together and present to their peers and explanation of how the sentence models the grammatical concept

of the week and why it is effectively written.

of the week and why it is effectively written. - Challenge students to identify a mentor sentence in a reading from another class and subject. Ask them to articulate what the grammatical concept achieved in that context.

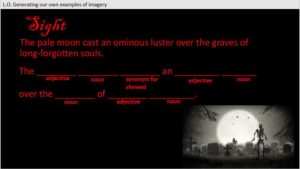

- Eliminate parts of the mentor sentence in a Mad-Libs style fill-in-the-blank and have students re-create their

own creative sentences using complex grammatical structures.

Any ideas you’d like to share? Comment below!